A step by step guide through the LogFrame

Filling out those sixteen cells of the LogFrame matrix can seem like a daunting task. On this page, we’ll show you how you can complete your logframe. However: it isn’t recommended that you design a project on the fly, as you fill out the different boxes. In fact, gathering the right information from the people you’ll be working with; the general situation surrounding your project (the context) and its influence; what the best approach is; what the available means are, and so on is no mean feat. There are different approaches to gathering all this information, such as the Logical Framework Approach.

But for now we’ll assume that you have this information on hand. If you’re new to the logical framework, you can do this exercise by imagining a very simple project that has only one person involved (one stakeholder): you.

The phases that we’ll go trough are:

- Designing the project’s main logic

- Identify risks and assumptions

- Say how you will know that things go as they’re supposed to

- Say where you will find that information

Before we explain this in some detail, just a little remark: when you start filling out the LogFrame, try to avoid overly complex sentences that include every little detail of what you want to express. Note down basic ideas and worry about the phrasing later. Once you’ve filled out all the cells a first time, you’ll probably end up shuffling things about, splitting objectives up or joining different ideas in a single concept. Once everything is in place, you can worry about putting it into a nice sentence.

Designing the project’s intervention logic

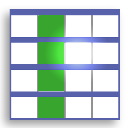

This means filling out the first column of the logical framework. Here you have two options: you can start by formulating a clear purpose for the project. This is the main reason why you’re undertaking the project in the first place.

This means filling out the first column of the logical framework. Here you have two options: you can start by formulating a clear purpose for the project. This is the main reason why you’re undertaking the project in the first place.

Often you’ll find that you have a clearer view of what you want to do (the activities) than what exactly you’ll end up with. So a second approach is first to write down what activities you have in mind in the bottom cell of the first column. Then you describe what these activities amount to, in other words what the tangible outputs or results are of your activities.

Together, your outputs/results lead to the definition of a single purpose for your project. This purpose solves the main problem. Its effects are immediate from the moment the purpose has been achieved. But there may be effects on a longer term, and often on a larger scale. After a while, your project may have an impact on more people and more problems than when you finished your work. These realisations are described in the top cell, and are called the goals of your project.

Example:

| Goals | |

| 1. | Improved hygiene of all family members |

| 2. | Improved social relations |

| Purpose | |

| 1. | Bathroom is renovated in 3 months |

| Outputs | |

| 1.1 | New plumbing is installed |

| 1.2 | New bath, shower and washing basins are installed |

| 1.3 | New bathroom tiles on the walls and on the floor |

| Activities | |

| 1.1.1 | Remove old pipes and drains |

| 1.1.2 | Install new pipes |

| 1.2.1 | Choose new bath, shower, shower curtain and washing basins with design expert (wife) |

| 1.2.2 | Install bath, shower and washing basins |

| 1.3.1 | Remove old tiles |

| 1.3.2 | Tile walls |

| 1.3.3 | Tile floor |

| 1.3.4 | Hang up shower curtain |

To identify the vertical logic of more complicated projects, you should use a methodology to identify the stakeholders and their needs, formulate problems and solutions, order them and agree on objectives and a planning. Take a look at the Logical Framework Approach or Results Based Management for more information.

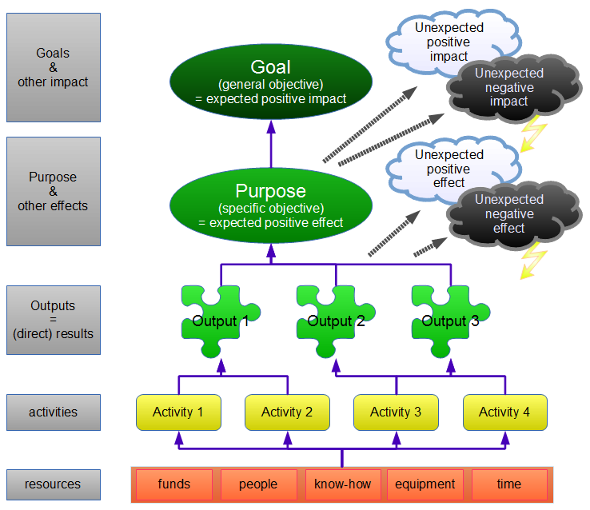

Output, outcome and impact

The logical framework allows you (and stimulates you) to see beyond the direct results (or outputs) of your activities. To achieve your project’s central objective, you use resources and do activities that produce tangible results or outputs. The main objective or purpose of your project is the outcome that you expect after all your efforts. But your project may lead to other outcomes, some of which you may have expected, but other you haven’t foreseen. These outcomes may be positive or negative.

For instance you can do a project with the purpose of providing water to the population of a village. You organise people and mobilise resources to build (activities and means) a water storage basin (output). As you expected, the village now has year-round access to water (outcome). Other expected outcomes may be that a lower percentage of livestock dies, so people also have a higher income. An unexpected outcome may be that neighbouring villages are attracted to this water source, which may lead to competition and conflicts.

While the outputs are visible as soon as the activities that created them are finished, outcomes generally come along when the project is well underway and heading towards the end, or even after the project has been completed. On a longer term, and a wider scale, the project can have a wider impact on the local society. Again, such an impact can be both expected or unexpected, and both positive or negative.

To continue with the water basin example: the easy access to water may free the women of the village from walking long distances to water holes. This way they could have more time for other activities and raise more income for their families. With more income, children can go to school, there is money to pay doctors or buy medicines, or the family can invest in better housing. In this case, improving access to water has a positive impact on education levels, health and housing conditions.

The goal(s)

A goal is an overall objective – generally a problem that is situated on the level of the (local) society as a whole – that the project contributes to. Achieving the project’s purpose won’t be enough to solve this problem. Many other things need to be addressed and solved before this goal will be achieved, but your project makes its own contribution.

A goal is an overall objective – generally a problem that is situated on the level of the (local) society as a whole – that the project contributes to. Achieving the project’s purpose won’t be enough to solve this problem. Many other things need to be addressed and solved before this goal will be achieved, but your project makes its own contribution.

The goal serves as a point of reference or a framework for your project. This is important to verify that your project serves the larger good and benefits the society as a whole. You should think about how your project relates to the efforts of others: local and national authorities, other NGOs, the local civil society, religious institutions, local and international businesses and other actors. Are you working with the forces of change, or against them?

When you formulate your goals, make sure that they are not too ambitious, too broad or ‘too far away’ from your project. When your project’s purpose is to provide drinking water in a certain region, the link with the goal of ‘reducing the negative effects of globalisation’ may be too far fetched. ‘Improving people’s health’ in that same region or in that country is a more realistic goal. The idea is that your project makes a significant contribution to that goal.

For international development, an important tool for the alignment of assistance are the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers that are developed by national governments. These documents explain the government’s development strategy, but also provide a framework for donors and international development actors to align their projects with the national policy and with other actors.

Because the goals are bigger than the scope of the project, they are also outside the control of the project. Their achievement doesn’t depend entirely on your project or the organisations that are involved.

The purpose

The purpose is the change that you expect in the target group’s situation at the end of the project. It is the reason why your project was developed in the first place.

The purpose is the change that you expect in the target group’s situation at the end of the project. It is the reason why your project was developed in the first place.

The scope of the project is defined by the purpose: who will benefit (how many people, what gender, age, social group); what is the time-frame; what is the area of intervention. Again, the relation between the purpose and the goal(s) is important: when the purpose is realised it should make an real contribution to achieving the goal. On the other hand, the purpose has to be realistic in view of the limitations of the project and of its participants (and their means), and in view of the context (risks, assumptions)

Generally, it is said that a project should only have one purpose, but in some cases projects can be so complex that they involve multiple purposes. In that case it is generally a good idea to split the project up in different individual projects, each with its own purpose.

A purpose (like a goal) is formulated like a state that is achieved, for instance: 'All children in the Tizandat district aged between 6 and 15 have access to basic education before 2015'.

When you formulate the purpose, make sure that it is realistic and achievable. Together, the outputs of the project should reasonably lead to the realisation of the purpose.

The outputs

Outputs are tangible results created as a consequence of the project’s activities. Together, the outputs lead to the achievement of the project’s main purpose. The purpose is the situation you hope to achieve when the project is finished. The outputs are goods, services and so on that you want to create over the course of the project. As such, the outputs are – in principle – completely under your control.

Outputs are tangible results created as a consequence of the project’s activities. Together, the outputs lead to the achievement of the project’s main purpose. The purpose is the situation you hope to achieve when the project is finished. The outputs are goods, services and so on that you want to create over the course of the project. As such, the outputs are – in principle – completely under your control.

At this level, the project logic is the strongest: you invest means (inputs) to do the activities, and the activities will lead to concrete outputs. There is a direct cause and effect: you do the activity (or you go through a process that combines different activities) and you get the output. This also means that you are fully responsible for achieving the outputs.

Outputs are formulated like a state that is achieved, not like an activity. For instance: 'All elementary schools in the Tizandat district are rehabilitated by 2013'.

If you write ‘Reconstruction of school buildings in the Tizandat district’, you formulate it as an activity, the act of reconstructing. Rather, you want to express that by the end of the project this action is finished and that the buildings are complete and shiny and new.

It is important to verify whether all outputs necessary to achieve the purpose have been identified. On the other hand, you should also refrain from adding outputs that may be nice, but have no direct link with the purpose. Often during the process of formulating the project with local partners and stakeholders, people have the tendency to say ‘while we’re at it, can’t we also include this or that nice idea’. They want to make good use of the(unique) opportunity that a donor or partner wants to do something in their area, and try to insert additional small projects.

Make sure the outputs that you’ve identified can be achieved with the resources at your disposal (or the means that you hope to achieve through a donor or other financers).

The activities

An activity is an action that transforms inputs (labour, knowledge, equipment, raw materials, time) into planned outputs within a specified period of time.

An activity is an action that transforms inputs (labour, knowledge, equipment, raw materials, time) into planned outputs within a specified period of time.

Sometimes, one activity is sufficient to get the desired outputs, but often you have to go through a series of activities. When you have to go through the same series of activities or tasks every time you want to get an output, you can define them as a process. In the logframe, each output has one or more activities/processes.

Activities have to be planned over time, to make sure all the outputs are obtained in the course of the project. Some activities can’t start before others, because they need the outputs that the previous activities produce. This means that when the first activity has a delay (started too late or takes more time than planned), the second one will also be delayed. This can cause a cascading effect and in the end the outputs aren’t realised within the project’s duration.

In other cases, activities aren’t dependent of each other, but planning too many activities at the same moment can create an overload for the project team. In such a case, activities will have to be postponed, but this means that the project’s planning goes out of the window and again by the end of the project you may find that not all the outputs have been realised.

Making a good planning also means that you make sure every activity is alotted the necessary time.

When establishing your logframe, make sure that all the key activities that are needed to obtain an output are listed, but don’t loose yourself in listing every little thing you have to do. For instance, routine administrative tasks are normally not included in the logframe. Contrary to outputs, purposes and goals, activities are formulated as an action: you do something.

Identifying risks and assumptions

When you’re planning a project, you tend to be optimistic about its progress. You envisage what you have to do and to what beautiful results this will lead. You don’t want to think about all the nasty things that can happen.

When you’re planning a project, you tend to be optimistic about its progress. You envisage what you have to do and to what beautiful results this will lead. You don’t want to think about all the nasty things that can happen.

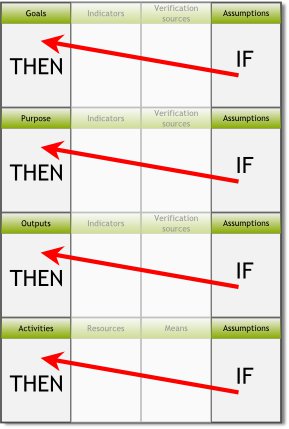

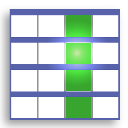

But there are many things that can go wrong. The logframe helps you identify these risks and the assumptions that you make at each stage and level. This is the role of the fourth column.

The assumptions describe the situations, events, conditions or decisions which are necessary for the success of the project, but which are largely or completely beyond the control of the project's management.

The fourth column and the first column have an if… then… relation. If the assumptions in column four are met, or if the risks do not occur, then we’ll achieve what we’ve set out to do in column one.

So starting at the bottom:

- If the basic assumptions (row 4) hold true ⇒ then we can do the activities as planned

- If we can do the activities and the assumptions of row 3hold true ⇒ then we will get the output (results) that we expected

- If we get all these results (outputs) and the assumptions of row 2hold true ⇒ then we will realise the project’s purpose

- If the purpose is achieved and the assumptions of row 1hold true ⇒ then we will contribute to the goals.

Identifying the risks and assumptions may seem easy, but there is more to it than meets the eye. The Results Based Management approach puts a lot of attention to this aspect, so check it out if you want more information.

When you’ve identified the possible risks, you have to assess what the probability is that each risk occurs:

- If the risk is very likely to occur and the impact on the project is grave (it is doubtful you can achieve the project), then you have to redesign your project to eliminate or significantly reduce this risk. If this is not possible you should really think again about doing the project.

- If the risk is likely to occur and the impact is important, but not life threatening, you should include it in the logframe and monitor the risk. If possible, you should try to influence the risk.

- If the impact of the risk is low, you shouldn’t include it into the logframe.

Like indicators, assumptions have to be verifiable. Don’t invent problems in your head.

Indicators

How you will know that things go as they’re supposed to?

How you will know that things go as they’re supposed to?

An indicator is a piece of information that tells you something about the state of your project, and how you are evolving towards (or not moving at all, or moving away from) an objective.

Indicators are often mixed up with the objectives themselves. Sometimes it is difficult to decide whether something is an output, or an indicator of the project’s purpose. But outputs, purposes and goals are the states you want to achieve at a certain point. Indicators tell you something about the way you’ve travelled so far to reach that point, they say something about change.

Defining a good indicator is a bit of an art in itself. To make things worse, there is no real consensus about what is a ‘good’ indicator. Some people insist on hard data in the form of numbers. But many things cannot be expressed in numbers, or only in a very artificial way. For instance, when you give psychological assistance to traumatised children in or after a situation of violent conflict, how can you express the state of the psychological healing process of a child in numbers?

The basic questions are:

- How will we (and the beneficiaries, and the donors) know that things are going as we expected?

- How can we see how far we are from achieving our objectives?

An indicator does not only tell you what progress you’ve made, but also how far you are from attaining the desired state. Compare for instance:

- The number of people that is treated in each health care centre (in area X), with

- The number of people treated in each health care centre has increased with 40% by the end of the second year of the project.

You’ll often need a series of indicators to verify whether you’re on track to reaching the objective. But you also have to make sure that there aren’t too many indicators, or that the monitoring system becomes too complex, too time-consuming, too expensive and too much of a general nuissance to the people working on the project. If the task of monitoring becomes too cumbersome, people will give bad or no feed-back at all.

An important question is that of the validity of your indicator, meaning: is your indicator measuring what it is supposed to. There are many things that can threaten the validity. Often, the indicator is so complicated that the people that have to use it don’t understand it, which leads to all kinds of confusion. Or the indicator contains complex concepts that are interpreted differently in various cultural settings, or by different people (e.g. ‘gender equality’, ‘ecological’, ‘participation’…) One thing and another may lead to the situation that when two people measure the same thing with the same indicator, they get different results.

If an indicator is too difficult, to expensive, too time-consuming or unreliable, you must replace it with another one (or other ones).

The question of accountability

One question that is often neglected is that of accountability. To start with, you need to know yourself what you’re doing and achieving. But otherwise: do you create a monitoring system to report what you’re doing and what you’ve achieved just for the donor’s sake? Or do you (also) create it to show to your beneficiaries and stakeholders what’s been done and achieved?

- If your system of indicators and reports focuses on reporting to the donors, we speak of upwards accountability.

- If your monitoring system and reporting system is focused on sharing with the beneficiaries (and stakeholders), then we talk about downwards accountability.

In principle, the two are not mutually exclusive. In practice, we see that most projects only have upwards accountability, to the lead-NGO and to the donors. Very often, beneficiaries and stakeholders are very poorly informed about the general state of the project. They only get information on a ‘need-to-know’ basis, meaning information that directly concerns them. They do not have the opportunity to give feed-back, to give their assessment and appreciation of the activities and the project as a whole. In this respect, they are not really empowered and become recipients in the project instead of actors or participants.

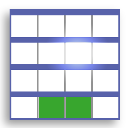

Verification sources

Where can you find the information that is needed to measure an indicator? Sometimes, the information is available from external sources, such as government statistics or studies made by universities, consultants and so on. Often, you’ll have to find the information yourself, through questionnaires, through observations by project staff, by means of your monitoring and reporting system.

Where can you find the information that is needed to measure an indicator? Sometimes, the information is available from external sources, such as government statistics or studies made by universities, consultants and so on. Often, you’ll have to find the information yourself, through questionnaires, through observations by project staff, by means of your monitoring and reporting system.

Verification sources have to be able to provide information that is readily accessible, reliable and up-to-date. This last element is often a problem with official statistics.

As for reliability: don’t believe any number you come across in a report or in (official) statistics. It’s wise to combine and compare information from different information sources. Sometimes the available information may not be specific enough. For instance, a national average may hide important differences between different parts of the country.

The means of verification determine to a large part the cost of your monitoring system. Information may be difficult to find or to get access to. It may require a big effort in terms of human resources and/or time to get the information that is needed. Again, if it becomes too costly you should probably reconsider your indicator(s) or your monitoring system as a whole.

The project’s inputs: resources and budget

The inputs or resources are the things that are transformed into outputs (tangible results). When we talk about inputs, we generally think about money, staff, materials and equipment. But there are other things that are needed for a project: time, knowledge and information, space, infrastructure, communication/information channels (access to information) and so on.

The inputs or resources are the things that are transformed into outputs (tangible results). When we talk about inputs, we generally think about money, staff, materials and equipment. But there are other things that are needed for a project: time, knowledge and information, space, infrastructure, communication/information channels (access to information) and so on.

Make sure all the necessary resources are there and that the resources are adapted to the context you’re working in. Buying an ordinary car is not a good idea in places where the definition of ‘road’ is ‘a long strip in the forest where there are no trees or really big boulders’. Inkjet printers have a notoriously short lifespan in hot desert countries. Highly trained, highly qualified staff may be difficult to find in certain countries, or not willing to go live and work in very difficult, poorly paid circumstances. Time is relative: it slows down when you travel near light speed and when you do projects in certain countries and regions.

The necessary resources for the project are generally placed on the bottom row of the logframe, next to the activities (below the indicators of the outputs, purpose(s) and goals). For each resource, you have to mention the quantity, a short description and the cost (under budget).

All the resources come at a price. In the third column of the bottom row you can put the estimated budget for each of these resources. Both for the resources and the budget, the rule is that you don’t specify every little thing you need. The idea is to give an indication of the main resources, costs and investments. A detailed overview of every item in the budget can be found in the project’s budget (in a separate document).

Talking about causality: for a donor it is very important to know that the inputs he finances are used for the planned activities (that he approves) and that those activities lead to the planned outputs and – hopefully – to the purpose of the project. In other words: the donor wants to know that he gets what he pays for.